The Boring Engineer Manifesto

Ju Data Engineering Weekly - Ep 92

Bonjour!

I’m Julien, freelance data engineer based in Geneva 🇨🇭.

Every week, I research and share ideas about the data engineering craft.

Not subscribed yet?

Last year, I published less than usual: 14 posts.

Not because I ran out of ideas — but because I was busy building:

Helped 6 data teams build data platforms (some with AI, some without — still possible in 2025 😉)

Shipped my first public products and OSS projects:

Boring Data — Terraform data stack templates

Boring-catalog — file-based Iceberg catalog

Boring-semantic-layer — Ibis-based semantic layer

kurt — an IDE for writers (more on this soon)

Across all these projects, I had to make a lot of design decisions.

During the end-of-year break — helped by Miami’s sunny vibes 🌴 — I reflected on:

what actually worked

what didn’t

and the patterns I keep seeing over and over again

This post is less technical than usual.

I attempt to formalize the Boring philosophy.

(Slightly ironic to write this in a not-so-boring city 😄)

1 — Why Boring?

Because complexity is the default tendency of most engineering projects I see—mine included.

Not because teams are bad.

Not because engineers are careless.

But because of our constant craving for tools.

As a result, complexity naturally accumulates:

every new tool solves a local problem

most tools eventually become obsolete

every vendor wants to be the vendor (aka platforms)

every abstraction hides a detail… and introduces another

And let’s be honest: vendors are really good at developer marketing 🙂

This marketing-driven push nudges the industry into ideological dilemmas:

OSS vs SaaS

“Just use X, reduce TCO” vs “Vendor lock-in is evil”.

Snowflake vs Databricks

(no comment 😅)

Cloud vs on-prem

“Just use managed services—100 engineers worked on this button”.

vs

“AWS is down? I don’t care, I spent hundreds of days building my own setup”

The problem isn’t that these debates are wrong.

It’s that they’re often argued without context, which makes it extremely hard, as an engineer, to pick the right tool for the right situation.

2 — What Boring Engineering Is Not

Boring Engineering is not:

anti-innovation / conservative

anti-SaaS

anti-cloud

anti-complex systems

Boring Engineering puts complexity where you can reason about it and maintain it.

Not where only the original author can.

3 — My Mistakes

Mistake 1: Picking a tool too early

Demos always look good.

Tools always have edge cases—hidden corners.

So now I default to proven, boring choices—until the problem demands otherwise.

Here’s what my current default stack looks like:

Code interfaces? Python

Compute? a Linux VM + DuckDB

Storage? S3 bucket

ELT? dlt

Application database? PostgreSQL

Collaborative data platforms? Snowflake or Databricks

To-do app? A piece of paper in my pocket

Car? Renault Kangoo ^^

Mistake 2: Over-generalizing a solution

I’ve repeatedly tried to design “generic” solutions that would cover every future use case.

In practice, this often resulted in:

poor or useless interfaces

complexity hidden behind overly implicit abstractions

systems that were hard to understand, extend, or debug

Trying to hide complexity doesn’t remove it—it just moves it to places where users have less control.

This is what I’m trying to achieve with the boring-* projects:

easy to install (e.g. pip install …)

no Docker required

smart defaults that work on day one, but can be tweaked later

ideally written in Python, making them easy for users to customize

Boring tools are designed to:

be learned in minutes, not weeks

fade into the background once adopted

If learning the tool becomes the work, the tool is the problem

(yes, certifications…)

Mistake 3: Designing for a future that never arrived

“We can scale to hundreds of terabytes.”

I’ve said it. I’ve built for it.

In many projects, features I was proud of later turned out to be over-engineered for scale (yes, Spark 😅).

The reality is simpler.

This is the core DuckDB message: a single node is good enough for a very large share of data workflows—in 99% of companies.

And this isn’t just theory.

I’ve verified it repeatedly across client projects.

From archi-tech to archi-preneur

The core of the Boring philosophy is being output-driven first.

Because of this, I now try to behave less like an architect—and more like an entrepreneur.

That means:

ship first

get feedback

tweak later

This is why the MVP mindset matters so much in data engineering.

MVP doesn’t mean trash output.

It means doing one very specific thing—and doing it really well.

When I start a project today, I avoid immediately building a generic solution.

Instead, I ask myself:

What is the question we need to answer first?

Then I plan backward.

Example:

Can DuckDB support the load?

Instead of building the full pipeline upfront, I generate data and quickly run a stress test.

Can dlt support this source?

I build this in isolation first, validate the assumptions, and only then move on.

The goal is to gather information early and push one-way decisions as late as possible.

Boring Design Philosophy

A boring system is:

as little code as possible

optimized for easy maintenance, not fancy features

understandable by the largest number of engineers possible

designed without assuming massive growth

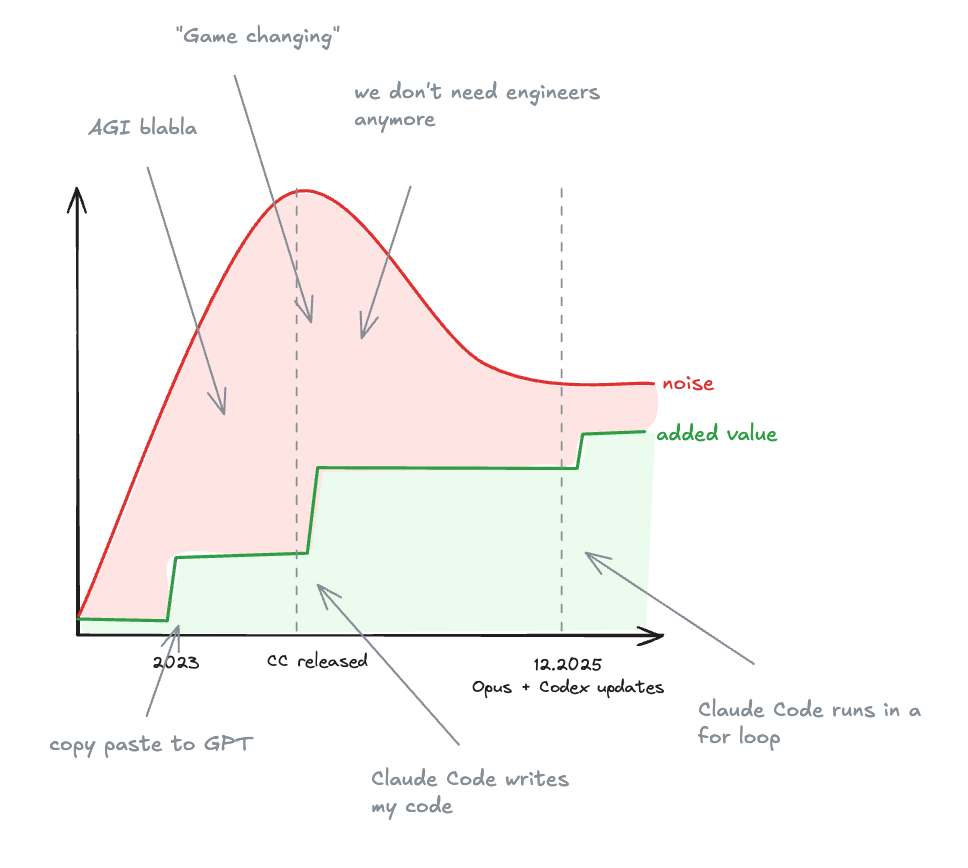

Is AI boring?

Boring Engineering isn’t anti-AI—it’s about using AI boringly: as a productivity multiplier, not a revolution.

These 2025 projects allowed me to deeply engage with the AI coding wave.

Like many of you, my social feeds has been full of “game-changing” claims.

I don’t know whether AGI arrives tomorrow.

Engineers won’t be replaced.

What is happening, though, is more interesting.

There’s a boring side to this wave—and that’s where the real leverage is.

For me, coding agents like Claude Code have completely changed how I work this year.

Over the last two years, I gradually moved from:

writing 100% of the code myself

to inline completions

to full prompting

Today, I spend most of my time coordinating agents and reviewing changes.

In 2026, the boring way to engineer might be to leverage AI.

You keep the design.

You outsource the implementation—while staying accountable for the result.

Outlook for This Year

AI has changed how we build.

Everything feels new, and everyone is still figuring out how to use these tools effectively.

This year, I want to get back to publishing weekly, as I (almost) managed to do in my first two years.

This newsletter will embrace the Boring philosophy, with a clear focus on engineering in an AI-first world:

Stress-testing data tools: understanding where tools work, where they break, and which ones are best suited to which problems

Leveraging AI coding assistants: practical workflows, patterns, and limits

I want this newsletter to be:

opinionated, but grounded in practice

focused on real-world trade-offs, not ideology

useful for engineers making decisions under constraints

Thanks for reading,

Ju

This was great thanks